In the spring of 1804, 26 year old farmer and laborer John London Kelley struck a deal with Kilborn Whitman to rent the 21 acre Lindsay farm and orchard on Oldham Street in Pembroke. Whitman, recently retired from the Pembroke ministry and now a judge and lawyer, agreed that John London Kelley’s rent would total $30 for the year, consisting of $15 cash due at the end of the year, and $15 worth of farm labor on Whitman’s behalf during the summer.

In 1804, John London Kelley and his wife Susannah Prince lived on the “Lindsay Farm” (the former homestead of Ephraim Lindsay/Lindsey) on Oldham St., Pembroke, Mass., which they rented from Kilborn Whitman. In the 1831 Map of Pembroke, African American/Mattakeeset Indian Martin Prince lived on the farm. Map courtesy of the Boston Public Library.

Kilborn Whitman. Image courtesy the Pembroke Historical Society.

John London Kelley found the terms agreeable, and settled his new young family on the farm, including his common law wife, 19 year old Susannah Prince, and their infant daughter Sarah. John London Kelley was the son of former Bridgewater slave, Kelley/Calley London Brewster and Margaret Stewart (likely of African and Mattakeeset Indian heritage), who settled in Hanson after the Revolutionary War.

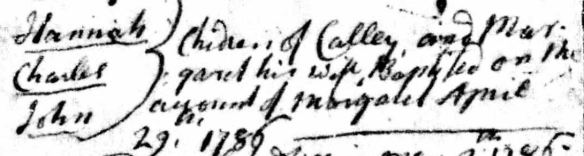

John London Kelley was baptized by Rev. Gad Hitchcock in the Hanson Congregational Church on 29 April 1786, along with several of his siblings.

29 April 1786 Baptism of siblings Hannah, Charles, and John, children of Calley and Margaret. They were baptized by Rev. Gad Hitchcock in the Hanson Congregational Church.

Susannah Prince had been born in Maine in 1785, the probable daughter of Pembroke “mulatto man” Sylvester Prince and his wife Rhoda Caesar (the daughter of a Marshfield slave father and Wampanoag Indian mother), who returned to the Hanson/Pembroke area during Susannah’s childhood. Summer arrived, and John London Kelley brought in the harvest to support his family, as well as Kilborn Whitman. Grain, root vegetables, and apples lasted the family into the winter.

One cold night in January 1805, an acquaintance, Benjamin Bates of Hanover, appeared at their door. Bates had overdue debts and had recently heard about a job opportunity to work as a sailor aboard a ship. Bates perhaps drunkenly heard about the job at a Pembroke or Hanover tavern, because he apparently did not inform any relatives or friends about his sudden money-making intentions. Benjamin Bates was welcomed into John London Kelley and Susannah Prince’s home, where Bates asked to exchange some of his old clothes for food to take on his journey, then immeditately left for Plymouth or Boston port. Within several days, Bates’ friends began to speculate where he was, and rumors began to circulate throughout Pembroke and Hanover. It quickly became apparent that Benjamin Bates had last been seen at the Kelleys’ home on the “evening of his departure.” The Kelleys later reported that “suspicions were excited against [us], that [we] had murdered the said Bates and concealed his death; popular prejudice being excited against us, it was but a short period before we began to experience some of its distressing effects.”

On 7 February 1805, several Pembroke constables forcibly took the Kelleys from their home and brought them before a Plymouth magistrate, who deemed it suspicious that Bates had suddenly disappeared, was last seen at the Kelleys’ home, and that they had some of his clothes. They claimed they had no knowledge of any foul play, but the judge ruled that they should be imprisoned at the Plymouth jail until a trial. Plymouth’s jail at the time was a small wooden building on Court Street, and prisoners were required to provide their own supplies during their stay. The Kelleys were imprisoned for four months “in that cold and inclement season, without money and without friends to soften the rigors of our confinement.” Their juried trial was held in May 1805, in which the judge and jury determined that there was no legal evidence against the Kelleys. Since there was no proof of Benjamin Bates’ death, the Kelleys were released from prison.

Upon returning to Pembroke, however, they discovered that Kilborn Whitman had rented the Lindsay farm to another African American-Mattakeeset Indian, John Wood alias Pero, and his family. Whitman also then immediately sued the Kelleys for not paying their remaining part of the rent, for damages totaling $50 (much more than the agreed upon and partially paid $30 rent). Whitman won his case, and John London Kelley was forced to default on the payment. As John explained, he and Susannah experienced physical and mental strain during their imprisonment, due to lack of food, clothing, blankets and support: “weakened & debilitated by [our] long confinement [we] were rendered incapable of earning [our] bread by [our] industry, and have suffered many & great hardships in conveyance of said confinement, & have not been able to this day, to do that quantity of labor, [we] easily performed before : [we] feel [our]selves poor & depressed.”

Although now free, the Kelleys could not lift the cloud of suspicion their neighbors held. “It was in vain we solemnly declared our innocence; in vain did we attempt to prove, we came honestly by the cloths that once belonged to Bates, by saying we had exchanged them; we were accused and therefore were not believed; we were people of colour, and our hearts were adjudged as dark as our complexions.”

During the fall of 1805, Benjamin Bates “returned from sea, visited his friends, and confirmed by his declaration, all [that] we had said in our defence.” It was a bittersweet moment for the Kelleys: “thus we are relieved of the horrid epithet of Murderers, which has often assailed our ears & wounded our hearts; and which we must probably have borne in the minds of some, at least, if Bates had been lost on his voyage.”

With their names finally cleared, the Kelleys still faced debts owed from their period of imprisonment, and they turned to the Pembroke selectmen for support. Towns at that time were required to support any impoverished residents, of any color, who had been born there. But despite the fact that both John London Kelley and Susannah Prince had both been raised in Hanson (then Pembroke), neither had technically been born there, so the selectmen refused. However, the selectmen had recently heard that former slaves or children of slaves could sometimes receive support from the state, since it was the Massachusetts government and judicial system that had deemed slavery to be illegal at the end of the Revolutionary War. This tactic didn’t always work, and often the towns or former slave owners in Massachusetts who petitioned the Massachusetts government were denied and ordered to pay for the support of their elderly or impoverished former slaves themselves. This may have happened with the Kelleys’ case, which was withdrawn by the Pembroke selectmen shortly after submitting it in early 1806.

Feeling abused by their Pembroke neighbors, the Kelleys left Pembroke and moved to Maine for several years, where a son Charles was born. They then returned to Plymouth County, where John and Susannah were officially married in Hanover in 1810, and had several more children. They later found more welcoming neighbors in Plymouth, and on Betty’s Neck in Lakeville, which both had Native American and African American communities.

Sources: Harvard’s Antislavery Petitions Massachusetts Dataverse, “House Unpassed Legislation 1806, Docket 5794, SC1/SERIES 230, Petition of John London Kelley”; MA Vital Records; Plymouth Court Records Whitman v. John London Kelly; Plymouth County Deeds 101:42 Whitman to Pero.

Researched by Mary Blauss Edwards.

Thanks Mary. This was quite informative.

Patty & John